Wadawurrung Country

Kim-barne Wadawurrung Tabayl (Welcome to Wadawurrung Country)

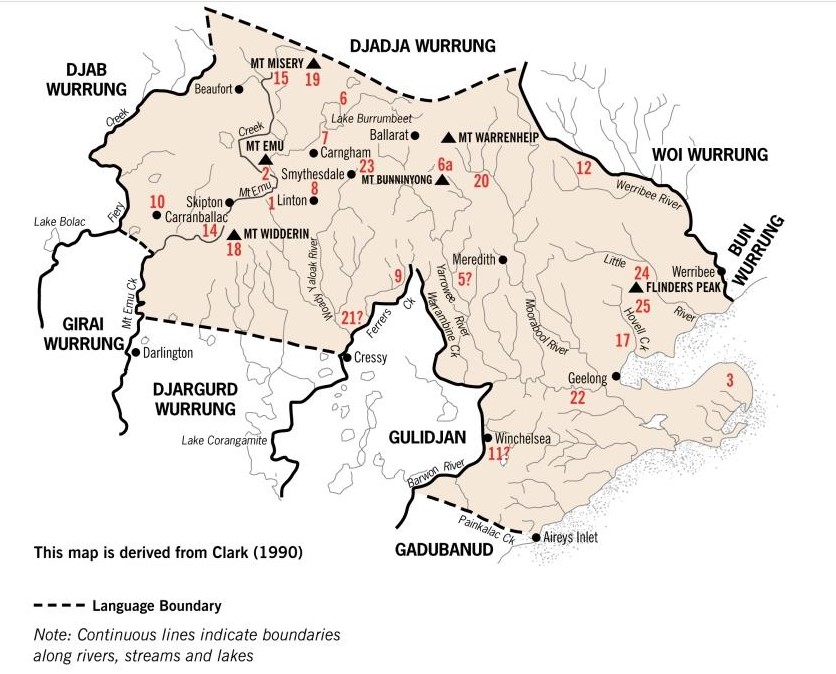

Torquay is situated on the traditional country of the Wadawurrung people who are part of the Kulin nation that surrounds Port Phillip Bay. Bunjil the eagle is their totem. Wadawurrung country encompasses the area from the Great Dividing Range in the north to the coast in the south; from the Werribee River in the east to Airey’s Inlet in the west and includes Geelong and Ballarat.

Neighbouring country

The Gulidjan people lived in the Lake Colac region. They occupied the grasslands, woodlands, volcanic plains and lakes region east of Lake Corangamite, west of the Barwon River and north of the Otway Ranges. Their land was bordered by Wadawurrung and Gadubanud country. They became known as the Colac tribe.

The Gadubanud people lived on the rainforest plateau and rugged coastline of Cape Otway. The centre of their land is thought to be Apollo Bay and occupation sites have been found on the Aire River. The extent of their territory is not entirely known however the abundant river estuaries on the coast provided rich food sources that included the wetlands at the Barwon River headwaters.

Concept of country

The Aboriginal concept of country was not property. If anything the country owned the people and they belonged to it and had a right and a duty to manage it; nor could they dispose of it, only their Law decreed who would inherit their country. Their spirit stayed on their country and they expected to die there. When an elder could no longer travel easily and death might come soon they stayed at a favourite place teaching ‘country’ to others. In 1837 it was observed “within the boundaries of their own country … [Aborigines] feel a degree of security and pleasure they find nowhere else – here their forefathers lived and roamed and hunted, and here their ashes will rest” (Gammage, 2012. p, 142).

History

The earliest evidence of Aboriginal occupation in the surf coast area is dated to the mid to late Holocene, approximately 5,000 years ago (Goulding, 2006). Aboriginal groups used the resource rich areas on the coastal margins and wetlands, moving seasonally between the coast and the productive plains of the hinterland. Coastal resources were important to the Aboriginal economies and some sites demonstrated an increasing development towards intensified use of marine resources and higher populations of people. Known Aboriginal heritage places within the surf coast area include shell middens on the coast and stone artefact scatters and some isolated artefacts on the adjoining plains and forested hinterland. Occupation sites along the coastline are evidenced by the middens, artefacts, scarred trees and rock shelters, with a fish trap at Loutit Bay and an ochre quarry at Point Addis. Aside from archaeological sites, places of importance to the Aboriginal people also include massacre sites, song lines, stories and family links to places. A major way that Aboriginal people related to their country was through art.

Buckley’s time (1803 – 1835)

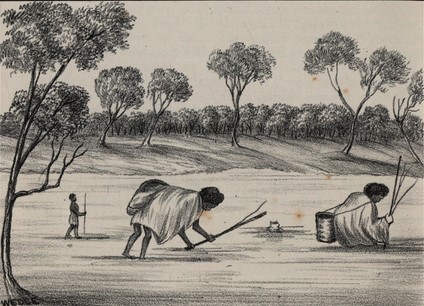

Accounts of the Aborigines who lived in the surf coast vicinity are first found in William Buckley‘s story of his life living with members of the local Wadawurrung people for 32 years. Food was found seasonally and the people with whom Buckley lived travelled widely to hunt and gather food. They would live at different places for days, weeks, months or longer. They went to Lake Corangamite, the land of Gulidjan people, for swan and swan eggs and also to Lake Modewarre. They went as far as Barramunga, near Apollo Bay in the Otway Ranges to swap food with the Gadubanud people. The women dug for roots with a yam stick and collected them in a dillybag or rush basket. One root called murning, the daisy yam, was a staple food very like a radish and with its bright yellow flower was seasonally abundant. The women would burn the grass to better see the roots. The uprooting of the soil in search of the yams has been called ‘accidental gardening’, as turning the earth over instead of diminishing the food had a tendency to increase it. The yams were washed and put into a rush basket then placed in an earth oven where they roasted, half melting into a sweet dark syrup. The earth ovens were constructed outside the dwellings by digging holes in the ground, plastering them with mud, and keeping a fire in them till they were hot, then removing the embers and lining the holes with wet grass. Food of all types was placed in the oven and covered with more wet grass, gravel, hot stones, and earth, and kept covered till they were cooked. The men hunted kangaroo, possum, emu, wild dogs and occasionally wombat; snakes and lizards were also eaten. Animal skins were removed with sharp stones and mussel shells and were worn as clothes and used as sleeping covers. They were sewn together with sinews and needles made from bone. Worn fur side out they repelled the rain, worn fur side in they provided warmth. Huts were made of branches of trees thrown across each other, with tea-tree and pieces of bark placed over as an additional shelter. However the local Wadawurrung people always returned to the Barwon River and the coast. Eels were caught at Buckley’s Falls, known as Boonea Yallock, on the Barwon River near Geelong where fat eels became trapped between the rocks. They camped on many sites on the edges of the swamps on the southern edge of Lake Connewarre where the lower reaches of the Barwon River forms a large shallow lake. Buckley also recounted that he witnessed fierce intra-tribal and inter-tribal hostilities that were sparked by hierarchy, and possession of food and spouses.

A surf coast camp

The lower reaches of Bream Creek (Thomsons Creek) east of Torquay and known as Karaaf was a large and well used camping place that extended over many acres on both sides of the mouth. Bream Creek and the shoreline west of it are fringed with dunes and inland there is a long series of swamps and marshes through which the creek meanders. The Aborigines constructed fish traps by erecting barriers made from the tea tree that grew abundantly. They put the barriers across the creek with openings where the fish swam in with the tide and into fish baskets placed at the openings. They also speared fish such as salmon and bream at night by the light of brush torches and caught eels also by spearing or using worms on a line. From the sea they gathered crayfish and shell fish from the broad shelf of submerged rock close to the mouth of Bream Creek. Warreners or periwinkles were a common shell fish found. Fish was roasted by putting thick layers of green grass on the hot ashes, and laying the fish upon them, covering them with another layer of grass, and then hot ashes on the top. This camp demonstrated a high population of people and its artefacts included axes, hammers, anvils and choppers. These tools were used to chop down the tea tree for fish traps and hammers to open the warrener shells. The abundance of food meant this camp was almost continually inhabited.

After colonisation from 1835

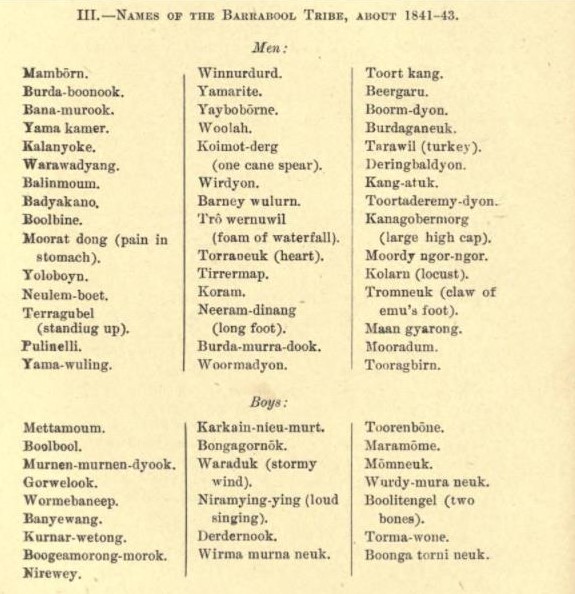

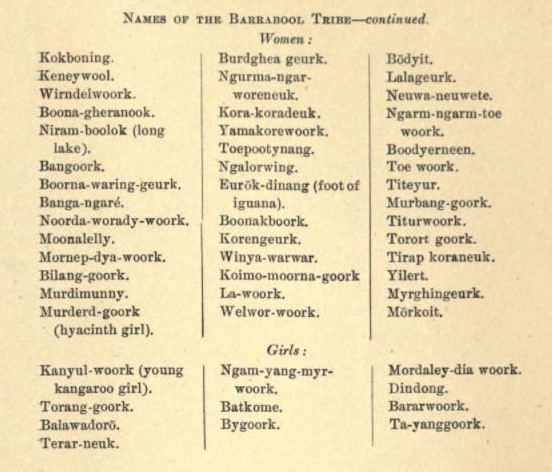

The next accounts of the Aborigines are after white settlement occurred in western Victoria from 1835 and their interactions with the squatters who took up large tracts of land for sheep farming. Deprived of their hunting grounds the Aborigines were attracted to the white men’s food and attacked animals and people. As a result there was loss of life on both sides. However George Russell of the Clyde Company relates that the Aborigines of the Geelong area “were quieter in their habits and more reconciled to the white population”. The local Wadawurrung people became known as the Barrabool tribe and in 1836 a muster to distribute blankets found they numbered 279. Reports of continued attacks on animals in 1838 resulted in the appointment of George Robinson as Chief Protectorate of Aborigines in Port Phillip, supported by an Assistant Protectorate Charles Sievwright and the Border Police to keep the peace. Sievwright moved with his family to live in tents among the Aborigines in the Geelong area. He was charged with protecting the Aborigines “from cruelty, oppression and injustice” and “from encroachments upon their property”. Sievwright complained to Robinson about Aboriginal deaths, as their traditional sources of food and clothing were depleted and also began a series of investigations into massacres of Aborigines. His determination to seek prosecutions for mass murders made him a most unpopular man with the government and culminated with his dismissal. Sievwright did however win considerable respect from the Aborigines who lived with him at several camps most having had little or no previous contact with Europeans. In 1841 – 42, Sievwright’s daughter Frances produced a useful list of the Barrabool language and the names of the local Wadawurrung people (Bride, 1889, pp 307 – 311). With sporadic supplies, Sievwright attempted food-for-work schemes, hoping to replace some of the lost traditional food with crops grown by the Aborigines themselves. For example within 5 years of white settlement the daisy yam was decimated as it was eaten by the sheep.

However attacks by Aborigines and stock thefts continued, and the squatters and the press blamed Sievwright for failing to stop them. By 1840 a meeting in Geelong complained about the continued attacks by the Aborigines and resulted in correspondence being sent to Governor Gipps. The correspondence said that the role of the Protectorate was ineffectual. The writers also stated they were sensitive to the Aborigines receiving humane and kindly treatment and that Aborigines had a claim on the government for support as their land had been seized. They believed the answer was providing reserves controlled by missionaries where food and clothing would be available, together with religious instruction in order to prevent “utter extermination”. Although this was implemented elsewhere a reserve for the Barrabool people did not occur until much later.

Inter-tribal hostilities continued during the 1840’s. In 1844 the Barrabool people were involved in a fight with the Buninyong people (Bride 1889 pp 94-96). In 1846 there is a report of a fight between the Barrabool people and Otway people. By 1850 the number of Barrabool people was greatly reduced and in 1854 they were assessed as being 34 adults and 2 children.

Anecdotal stories of the indigenous people living around Spring Creek (Doorangwar) are handed down from the early settlers of the area. In the 1843 when the first white child was born it was of great interest to the aboriginal people and during the 1860-1870s there are tales of camps along the creek.

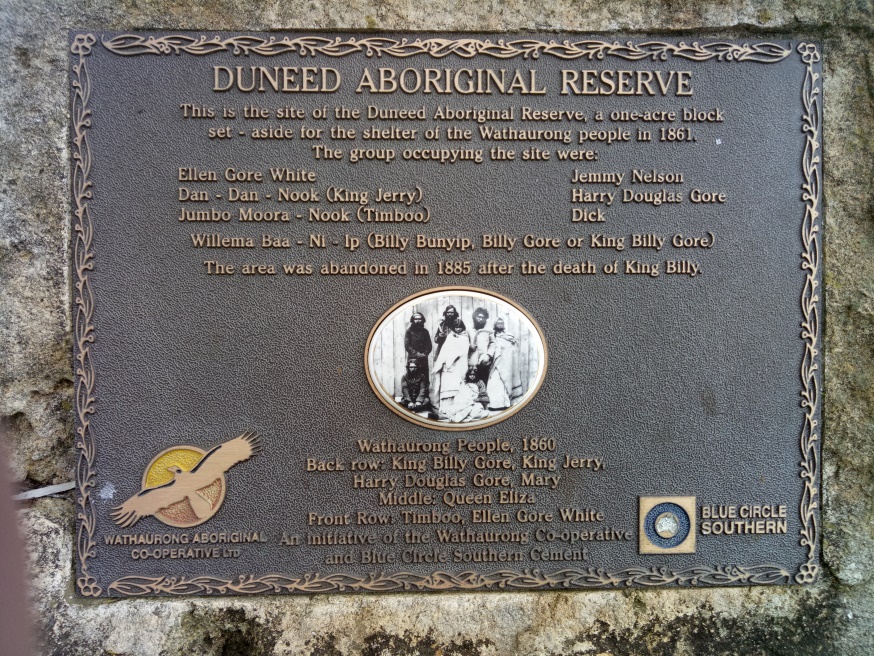

In 1861 a small one acre reserve of land was allocated to the local Wadawurrung people on Ghazeepore Road adjacent to Andersons Creek where six males and one female lived. The last member of the group was Willema Baa Ni Ip (c. 1835-1885), also known as William Gore and King Billy. He is the boy Wormebaanep in Frances Sievwright’s list of the Wadawurrung men and boys recorded in 1842. On the day Willema Baa Ni Ip was born his father had seen a mythical bunyip in the billabong and so named the child “home bunyip”. Willema Baa Ni Ip died in 1885 of tuberculosis in the Geelong Hospital aged 49 years and is buried in the Geelong Western Cemetery with other Wadawurrung members. Today Baanip Boulevard in Armstrong Creek linking Ghazeepore Road to the Surf Coast Highway is named for Willema Baa Ni Ip.

Today the traditional custodians of the surf coast area are descended from Wadawurrung people from elsewhere in Wadawurrung country; some may be related to the Barrabool people. The Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation the representative body for Wadawurrung Traditional Owners works to support their aspirations and protect aboriginal cultural heritage in accordance with the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

References

Arkley L. (2009). Charles Wightman Sievwright 1800-1855. Australian Dictionary of Biography. Available from adb.anu.edu.au

Australian Heritage Database Record at Australian Government. National Heritage List. Great Ocean Road, Victoria: History. Available from environment.gov.au

Bride, T. (1889). Letters from Victorian Pioneers. Public Library of Victoria: Melbourne. Available from the Public Library of Victoria

Clark, I. D. (1998). The Journals of George Augustus Robinson, Chief Protector, Port Phillip Aboriginal Protectorate, Volume Two: 1 October 1840 – 31 August 1841. Beaconsfield: Heritage Matters.

Dawson, J, (1881). Australian Aborigines : the languages and customs of several tribes of Aborigines in the western district of Victoria. Melbourne: George Robertson. Available from nla.gov.au

Frankel, D. (1982). An account of Aboriginal use of the yam-daisy. The Artefact. pp. 43–45. Royal Historical Society of Victoria: Melbourne (Unpublished manuscripts).

Gammage, B. (2012). The biggest estate on earth; how aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin: Crow’s Nest NSW.

Gott, B. (1983). Murnong—microseris scapigera: a study of a staple food of Victorian Aborigines. Australian Aboriginal Studies. 2. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Goulding, M. (2006). Indigenous heritage values: National Heritage List desktop study of the Otway Ranges National Park, Coastal Reserves and Alcoa Lease, Victoria. Report to the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra, ACT.

Massola, A. (1969). Journey to Aboriginal Victoria. Rigby: Adelaide SA.

Morgan, J. (1852). The life and adventures of William Buckley. A. MacDougall: Hobart. (Reprinted in 1980. Australian National University Press, Canberra). Available from openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au

Wadawurrung Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation. Available from wadawurrung.org.au/

Willem Baa Ni Ip. Available from djillong.net.au/traditions/tandops-stories/willem-baa-ni-ip

Wynd, I. (1992). Barrabool: land of the magpie. Barrabool Shire: Torquay. Available from the Geelong Regional Libraries.

1852 State Library of Victoria

Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Courtesy State Library of Victoria

Courtesy State Library of Victoria